Femininity Defined

Frances Hodgkins' Images of Women

19 November 2005 - 16 April 2006

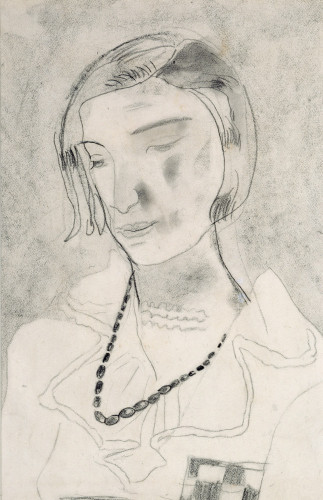

In the early part of her career, Frances Hodgkins often painted women. Whether resting on a fishing boat, doing the laundry or posing for a portrait, her female subjects are characteristically charming and feminine. Why do these pretty girls predominate? Was the quality or condition of being female of particular interest to her, or did Hodgkins’ own gender restrict her experiences to the world of women? Did she seek to understand her own social identity by painting women in the kind of feminine roles that she herself was just learning to adopt? Or was it just that her market dictated her subjects? And why did she cease to make images of women in her later life?

Looking at Hodgkins’ beginnings in Dunedin, it is her concentration on the figure that distinguishes her painting from the landscapes of her father, William Mathew Hodgkins, and the flower paintings of sister Isabel. Frances Hodgkins’ first exhibited paintings are of quaint elderly colonists, female servants and Maori women - the everyday Otago equivalent of the genre paintings of French and English peasants that she saw in magazines. Later, as her confidence and reputation grew, she painted the portraits of women from her Dunedin social circle. These were middle class fashionable women with whom she shared an interest in dresses, hats, hairstyles and gossip.

In the larger art world overseas that Frances Hodgkins read about and longed to join, hers was the kind of work that would consign its maker to ridicule. George Moore sums up this attitude in Modern Painting (1893): “it is just because man can raise himself above the sentimental cravings of natural affection that his art is so infinitely higher than women’s art.” Hodgkins said she went to Europe “to measure herself with the Moderns”. She quickly realised she must move on from painting her family and friends and set out to build her professional reputation by developing her Impressionist technique. In Paris, to her delight, she discovered Impressionism was l’art féminin and the world was ready for women who painted from their own experience. She exhibited in women’s exhibitions and won prizes offered to women by women patrons.

Back in Britain, while competing with much younger artists to be a “modern” in the twenties and thirties, Frances Hodgkins found she again had to contend with the idea that “woman artist” was a contradiction in terms. Writers describing her work often remarked on her gender or even worse, ascribed one to her style. Hodgkins must have been dismayed when in 1937, Clive Bell announced that the 68-year-old painter was “at her best when she is most herself and therefore most feminine.”

Hodgkins longed to have her art admired for its virility, and realised that bold colour and abstraction in painting were the desirable masculine traits that would assure her of a place amongst the avant-garde. By 1933, literal femininity had been replaced with its symbolic representation – flowers, eggs, urns, shoes and scarves – displacing figures of women with inanimate things. But her style had become fluid, romantic and expressive, and her “sly evasions” did not fool the critics. Eric Newton wrote in 1941: “That she is a woman is important. Femininity does mean something in art. It means, in her case, a quite hair-raising reliance on instinct, and a rather disturbing refusal to be logical or prudent”. Newton’s discomfort shows that feminine difference in Frances Hodgkins’ painting had finally found its mark.